Maîtrise Orthopédique

Mai 2017

COMMISSION PARITAIRE 1218T 86410 ISSN : 1148 2362

This year the 11th congress of the International Society of Arthroscopy,

Knee and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) is to be held in Shanghai.

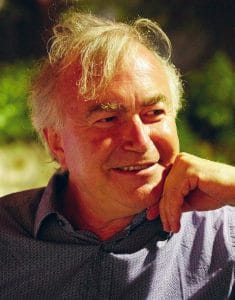

Presiding over the conference will be Professor Philippe Neyret.

Professor Neyret has been a frequent contributor to Maitrise Orthopédique,

and now, when he is at a turning point in his career, he has agreed to look back over the years

and tell us about his experiences in the realm of knee surgery.

This year the 11th congress of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) is to be held in Shanghai. Presiding over the conference will be Professor Philippe Neyret. Professor Neyret has been a frequent contributor to Maitrise Orthopédique, and now, when he is at a turning point in his career, he has agreed to look back over the years and tell us about his experiences in the realm of knee surgery.

This year the 11th congress of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) is to be held in Shanghai. Presiding over the conference will be Professor Philippe Neyret. Professor Neyret has been a frequent contributor to Maitrise Orthopédique, and now, when he is at a turning point in his career, he has agreed to look back over the years and tell us about his experiences in the realm of knee surgery.

M.O.: What does ISAKOS mean to you?

P.N.: It’s quite a young society in fact, it was born when the International Arthroscopy Association merged with the International Society of the Knee, the ISK. It’s very special to me, because Albert Trillat was one of the founding members of the ISK, alongside Pierre Chambat, Jean-Luc Lerat, Henri Dejour and others. He was the second president the first being Don O’Donoghue. And most of all – the first congress was held in Lyon, in 1979.

M.O.: Now it’s your turn to be president.

P.N.: Yes, I was voted in at a meeting of the General Assembly in Rio in 2011. I was very pleased and also very proud to have been chosen to join the ‘presidential line’ as second vice-president. I had the support of colleagues from continents and that meant a lot to me. I’d travelled a lot already, and I’d already served as consultant and then treasurer, as well as coordinating the Knee Committee for four years. When I’ve been president for two years and the Shanghai congress has ended, I’ll be a ‘past-president’. It’s been a long road and represents 20 years of work.

M.O.: What exactly does being president of ISAKOS involve?

P.N.: It involves spending a great deal of time organising and developing the society. But it also gives you some amazing opportunities. Per Renström, Paolo Aglietti and Roland Jakob co-opted me onto the Executive Committee, and, as soon as I had been nominated in Rio, Per took me aside and said: “Being president gives you real power in ISAKOS and you have to make sure you use it for the benefit of ISAKOS ». But you know this is really a team work.

M.O.: What in particular have you achieved during your presidency?

P.N.: ISAKOS’s image was primarily associated with sports pathologies and we wanted to put more emphasis on knee prostheses. So we split the old Knee Committee into two new ones: the Knee Preservation Committee, which deals with sportsrelated issues, and the Knee Arthroplasty Committee. Clearly, for the next decade, there will be an emphasis on knee replacements. But that’s not all. We’ve also created a Shoulder Committee and other committees, so that we can align what we do with the chosen strategy. And the strategy was redefined during a three-day stay in Florida just before the 2016 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Annual Meeting,with the help of strategy consultants, financiers, people from the industry and about 20 specially chosen members of the society.

M.O.: What else have you done?

P.N.: I have continued the work begun by my predecessor, Masahiro Kurosaka, John Bartlett and others who started the project JISAKOS, an official journal of ISAKOS , in response to demand from our 4,000 members, who wanted to have their own journal. The editor in chief is Niek van Dijk. We have been collaborating really well with the Journal of Arthroscopy, which our members receive free of charge. The Journal of Arthroscopy goes on being the ISAKOS official journal until at least the end of 2017. We are currently discussing the terms of our next partnership; it is fairly complicated, because our members are keen to see original articles including degenerative knees. Soon, under the chairmanship of Marc Safran, we will be launching what is going to be, in my opinion, a fantastic worldwide educational initiative. I can’t reveal the details at this stage, but I really must emphase that our website is truly remarkable and we are putting a lot of resources into the project, with the aim of conducting a global educational campaign focusing on the areas targeted by ISAKOS.

M.O.: The 2015 congress took place in Lyon – hardly any bigger than a little village compared with Shanghai!

P.N.: Perhaps, but there were still 4,100 people involved and it was a great success from both a scientific and a social point of view. We had a lot of support from the French Society of Arthroscopy as regards holding the congress in France. Frédéric Rongieras, my team and even my wife all worked hard for two years to make sure that we gave our friends and colleagues from all over the world the best experience we possibly could – we hosted representatives of more than 90 different countries altogether. As someone born and bred in Lyon,

holding the ISAKOS conference in Lyon meant coming full circle. For 2017, even though it clearly wasn’t the easiest alternative, I

was very keen to persuade the Site Committee to hold it in Shanghai. I am familiar with the needs and possibilities of Chinese surgeons because I’ve been there at least 10 times with René Verdonk and the sadly departed Jean Puget.

M.O.: Why those two in particular?

P.N.: With the help of my tutor, Henri Dejour, I obtained a professorship when I was 36 and became head of department at Croix Rousse hospital aged 38. I was very young and it was a real challenge, because I was no longer working in the same department as my old boss. Here I was in a paediatric surgery hospital and there was nothing there for knees – there wasn’t even a knee surgery kit! It was an incredible challenge and I devoted all my energy to it. But there was no one at the hospital that could give me any advice, and the experiences of my friends in the private sector were no help because they were in a completely different situation. And this was when two doctors working at the university hospital, Jean Puget and René Verdonk, whom I very much admired for their vision and humanity, agreed to go to China with me, and gave me lots of good advice. We had some really good times too. They told me not just to operate a lot but to travel a lot too.

M.O.: What was the purpose of these trips to China?

P.N.: It was just a combination of circumstances. Shortly before the beginning of the 2000s I had a Chinese assistant, Ling Ming. He was from Xi’an, in Shaanxi Province, where they discovered the famous Terracotta Army. Ling Ming was in Lyon for two and a half years but he was extremely shy. He suggested I travel to China, and, to tell the truth, I’d always been interested in China because I used to play table tennis at quite a high level. In fact, every time I’ve been to China my hosts have thoughtfully organised a friendly game of ping-pong with world champion teams and given me the Chinese team T-shirt. But the main reason was that Lyon was twinned with Canton and the Rhône-Alpes region had contracts with Shanghai Province. I was able to get funding for my trip to China from the Rhône-Alpes region and I was able to bring 15 or so Chinese fellows to Lyon. They were opening orthopaedic implant R & D centres in China at the time, and I saw the most spectacular changes take place: departments that had done just four knee replacements one year were doing 500 the next!

: It’s easy to see why China wanted to improve its surgical prowess 20 years ago – but why choose Lyon?

P.N.: It is said that Lyon’s Franco-Chinese Institute once hosted Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping for two years – before they became eminent Chinese leaders. But there is also a historical relationship between China and Lyon, because Lyon was the last stop on the silk route. So all these things helped to build Lyon’s special relationship with China.

M.O.: How many times have you been to China?

P.N.: About 15 – and I went to Shanghai practically every time. I’ve been to Peking three or four times, and to Xi’an four or five times, and I’ve also been to lots of towns near Shanghai. A number of my previous Chinese fellows are in Shanghai; some are running the Second Medical University of Shanghai, Renji Hospital, while others are at Number One Hospital. What’s fascinating about it is the number of patients they treat. For example, on one of my trips, they’d built a consultation centre where they expected 2 million consultations to take place the following year!

M.O.: What do you think of the level of orthopaedic surgery in China?

P.N.: I think it varies, which is hardly surprising considering the size of the country and that there are 130,000 orthopaedic surgeons. But in Shanghai standards are the same as here and it’s really important to share our knowledge. ISAKOS isn’t being held in Shanghai just by chance. Our colleagues in Shanghai are very sports-orientated and they were greatly inspired by the Olympic Games. Things are clearly going very quickly over there

– the centre of gravity is moving eastwards and, even if western medicine is still slightly ahead of its Asian counterpart, the energy China is putting into it means that one day soon they are going to overtake us.

M.O.: What do you see as your major contributions to knee surgery?

P.N.: Perhaps I haven’t been an innovator or a creator like Gilles Bousquet, but I feel I’m more like Henri Dejour, who analysed situations much more. I have his thoroughness when it comes to assessing results. I think that the important thing is to make the right choices and steer one’s students and teams in the right direction. What affords me the greatest satisfaction is knowing that I’ve rarely made a wrong decision when choosing which implant or technique to use, be it for an osteotomy or a unicompartmental knee replacement. I’ve managed to identify a certain number of indications that have proved to be valid for our area, for our patients in the city of Lyon, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they apply elsewhere.

M.O.: Can you give us some concrete examples?

P.N.: In ligament surgery, I have never stopped doing extra-articular plasties. Ever since I first became registrar, in 1988, I have carried out ACL [anterior cruciate ligament] grafts using a bone-patellar tendon-bone composite graft, and in a certain number of cases, but not always, I associated this with extra-articular augmentation. This brought me into interesting discussions in the ACL study group and eminent foreign colleagues who had written books against extra-articular plasty. Nevertheless I carried on doing it, and the fact that my results were reproducible reinforced my belief that it was the right choice to make. Later I saw extra- articular plasties being promoted again, almost like a craze.

M.O.: In cases of anterior instability, what criteria do you use when deciding whether or not to perform an extra-articular plasty?

P.N.: Firstly there must be significant laxity. With chronic laxity, where an internal meniscectomy has often been performed, there is major anterior tibial translation and it is difficult to control laxity in such patients with ACL reconstruction only. The second criterion is an explosive pivot shift, because, like it or not, a Lemaire procedure is very effective against pivot shifts. The third criterion concerns revision of a failed ACL graft: no matter how skilled the surgeon, it is always difficult to perform a perfect ACL reconstruction covering all insertion sites. In such cases, residual laxity may remain and it can be very useful to have an extra-articular augmentation. It could be also useful also in some mild rotatory instability after ACL reconstruction. Moreover, in young women under the age of 20 who have ruptured their ACL, the reconstruction failure rate is probably more than 20%. So for such patients this kind of additional plasty cannot fail to be useful. There is one more indication for extra-articular plasty

– it is for patients who play risky sports like rugby and football or sports involving pivoting or collisions, particularly if they plan to return to the sport within six months. In such cases the graft may not have had enough time to be perfectly integrated.

M.O.: Another concrete example of contributions you have made?

P.N.: Unicompartmental knee replacements have always been very popular in France, thanks to Philippe Cartier and Gérard Deschamps, but in other countries they were performed relatively little except perhaps in Scandinavia and the UK. Here too I followed in the footsteps of my elders: David Dejour and I analysed patient outcomes and we stressed quite emphatically that it seemed to work better on the lateral compartment than on medial compartment It turns out that this is indeed the case, and that unicompartmental replacements to the outer side of the knee work very well, whereas on the inner side outcomes are far less convincing, with a certain number of failures or incomplete results. We went on performing this procedure regularly, whereas others abandoned the technique. And then all of a sudden, about five or six years ago, hundreds of surgeons started doing them and it became quite a craze, particularly with the advent of out-patient surgery, which means six or seven operations can be performed in a morning and patients can go back to work fairly quickly. What really interests the patients is the immediate result and the financial cost, rather than how long the implant will last, which is what concerns us. By analysing the results and the accumulated experience of our predecessors, we tend to indicate this procedure in around 15–20% of cases, and I feel this is something that can reasonably be passed on in a country like France.

M.O.: Who would be the ideal subject for a unicompartmental replacement?

P.N.: I usually say an elegant old lady. Someone who can bend her knee well, and who is fairly slim and therefore needs to be able to bend it properly. In other words, she’s fairly dynamic but won’t be putting any particular strain on her unicompartmental prosthesis. So, a fairly stylish old lady who has high expectations and consults a doctor in the early stages of osteoarthritis.

M.O.: What was your first choice for total knee replacements?

P.N.: I chose to implant cemented, posterior-stabilised prostheses. This was because I needed a ‘one size fits all’ procedure, that could be performed regularly in any situation, with a reasonable stock of implants. I made the choice based on practical concerns, but it also meets medical and financial criteria. Even with such considerable hindsight, I have absolutely no regrets about choosing this type of implant which has proved to be highly reliable. I think that, compared with other specialities, we orthopaedic surgeons have had to deal with extremely complex situations and spent huge amounts of time trying to simplify our surgery. I feel it’s quite unique

– to have spent so much time with manufacturers, trying to develop high-performance ancillary instruments that will make our lives easier and ensure good outcomes for our surgery. Some people say that doing a knee replacement is easy and only takes an hour. And it’s true – but it only takes an hour because lots of surgeons and engineers have spent vast amounts of time thinking about how it might be done so quickly.

M.O.: At the end of the day, what gives you the most satisfaction?

P.N.: On the technical side, it’s having successfully developed, some 25 years ago, the idea of an asymmetrical cut in total knee replacements with extra-articular deformity and introduced performing a combined arthroplasty and osteotomy during the same procedure. Having perfected partial reconstruction of the extensor apparatus in cases of chronic rupture. But also having promoting with David Dejour the management of patellofemoral disorders, initally proposed by Henri Dejour and Gilles Walch, the now famous « menu à la carte ». Having continued to treat the young adult degenerative knee conservatively, by suggesting an osteotomy. And, last but not least, having gathered together, in a book for younger colleagues, all the techniques used by the Lyon school. The books have been translated into English, Greek, Polish, German, and, of course, Chinese. But I think what makes me proudest of all is having appointed two university professor-hospital consultants, and, with their help and that of their predecessors, such as Tarik Ait Si Selmi and Guillaume Demey, having organised a department that runs like clockwork. To tell the truth, we are still making improvements, but in light of the constraints imposed on us I feel I’ve come as far as I can – I’ve reached the asymptote, if you like – in terms of making any further contributions to my department.

M.O.: Isn’t it a little sad to think you’ve done all you can?

P.N.: That’s not how I see it. I’ve been head of the department for 20 years now and I’ve devoted a lot of time to it and even more

to promoting the Lyon School of Knee Surgery. Between ourselves, it’s a very heavy responsibility. Of course I’m not the only heir, but I’ve always felt that one day I would have to hand back the keys, and that when I did the school should be in great shape. And it is, thanks to a group of people: Pierre Chambat, former president of ESSKA, European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy, Gérard Deschamps, David Dejour, who, I am delighted to say, will soon be president of ESSKA, Michel Bonnin, the next president of the SFHG, French Society for Hip and Knee Surgery, and also some more recent stars of the school, such as Elvire Servien, Sébastien Lustig and Roger Badet.

M.O: Why retire then?

P.N.: I do not retire! I continue to work but differently. I loved what I do and still love it. I am magnificently busy both locally and abroad. But I’ve never forgotten the very moving note Gérard Saillant sent me when he stepped down from being head of department at La Pitié hospital: “I have always been the first to arrive at the department and the last to leave – but when you can’t do it any more it’s time to step down.” That’s what’s happened to me, but I am not at all worried about what will become of the department, because I know much already rests on the shoulders of my two associate professors.

M.O: So you don’t want to be a head of department any more?

P.N.: No. After 20 years of running my department, supporting research, organising symposiums, the Trillat Tuesdays, chairing the ACL study group from 2014 to 2016, and publishing numerous documents, I’ve decided to take a temporary leave of absence, so that I can concentrate on ISAKOS, and, to an even greater extent, EFORT. Because I am also the general secretary of the EFORT Foundation and I want to be able to get more involved. I want to go on teaching and of course practising surgery, but primarily in a different way and not in my Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, and without all the responsibilities of a university hospital post.

M.O.: No doubt, but doesn’t a university hospital post provide the best opportunities for doing those things?

P.N.: It’s a privileged position but it’s increasingly demanding and subject to increasing regulation. I am sure that Elvire and Sébastien will be able to take the Lyon school further than I could. They have the energy of youth and I think they’re ready. They have time, they have years ahead of them. Not only that, but I don’t yet know how this interlude of mine is going to end. I haven’t made detailed plans as yet, but I want to try something different. Apart from working with learned societies, I want to practise my profession – the profession I have learnt, the profession I know and love. That means working in places where what counts most is providing excellent care, rather than looking primarily at how much it costs.

M.O.: But where will you find this El Dorado?

P.N.: To be honest, I feel comfortable in any country where time is spent on clinical practice rather than administration or pseudo-evaluation. There are still many such countries – some people call them ‘new’ or ’emerging’, but I think the world’s centre of gravity has moved to the East. That’s where I can feel the world’s heart beating. They’re forever trying to fool us with their stories of recession, but, on a world scale, growth is still happening. So I’d like to try it out for a few months and then… come back. We university professor-hospital consultants can still do that. I want to feel freer, to not have to justify economically every procedure, every trip, every educational initiative – I want to know what that feels like, even if it’s only for a few months or a few years.

: And is it easy to leave when you’re 59?

P.N.: Yes and no. Yes because I already feel relieved at the thought of no longer having so many responsibilities and obligations. Not only that, but my wife, Isabelle, who is from Algiers and loves travelling, is highly enthusiastic. We’ve always loved travelling. For someone who hates sealess cities and public-sector employees, she hasn’t had it easy in Lyon! No because it’s not always easy to do things differently, and also because a leave of absence is very strictly regulated by the authorities. It’s understandable and you just have to make do… But having said that, I’ve seen some of my former hospital colleagues in Paris make the move into private practice most satisfactorily.

M.O.: Is that what you’d like to do?

P.N.: No, what I want to do is practise my profession differently, in a different environment. I want to promote our school and our ideas, using the image of quality and innovation that is associated with French orthopaedic surgery, but I also want to promote the use of French implants and instruments, invented by surgeons and engineers, in the field of knee surgery. And I want to be even more involved in educational initiatives organised by learned societies.

M.O.: Do you have any regrets?

P.N.: I would have liked to have been able to do all these things in France but that would mean ignoring the constraints imposed by being a public servant. There is no doubt that I work for a major institution, but the emphasis on making savings and pooling resources and the drive towards interchangeability are overriding everything else.

M.O.: What’s your dream?

P.N.: My dream is to go on working in knee surgery, without the pressures that have come to bear in recent years, and to practise the profession I love in a way I recognise, knowing all the time that my department is in very good hands. I’d like to work with our learned societies and reliable manufacturers on developing innovation and education. I am particularly keen to maintain and develop the links I have forged, not just with my French colleagues, such as Elvire and Sébastien, but also with my 25 clinical leads, the 110 residents who have worked in my department and the 400 foreign visitors we have had – not to mention, of course, the Lyon School of Knee Surgery. But probably the most exalting thing of all will be to focus on surgical values again and to live a new adventure with Isabelle, my wife, and show our children how important it is to be free and remain faithful to your convictions… and to go on exploring the world in all its diversity. I am still curious, still passionate.